The Day of the Christianization of Poland, April 14

The degree to which the secular and sacred realms are intertwined in Poland is high. Religion – Roman Catholic – is strongly connected with politics. There were changes of authorities after 1989, and different political options were in power, but in no case was this intertwining weaker. The influence of the Catholic Church on political decisions during these more than three decades is clear, touching many spheres of our everyday life. A symbolic example of this is the establishment of the Day of the Christianization of Poland in 2019. On April 9 of this year, an act was published in the Dziennik Ustaw, accepted on February 22, to establish April 14 as the National Day of the Christianization of Poland.

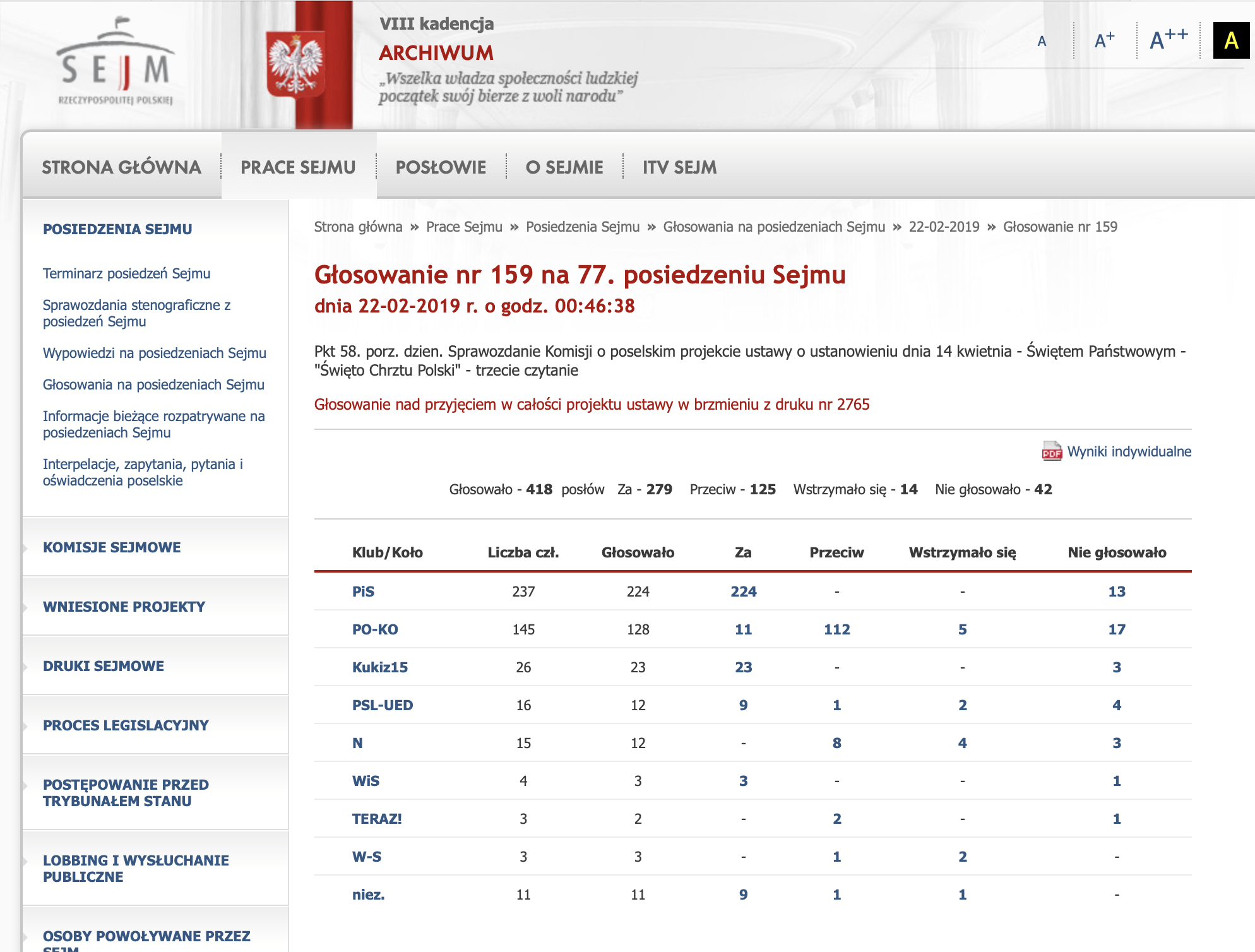

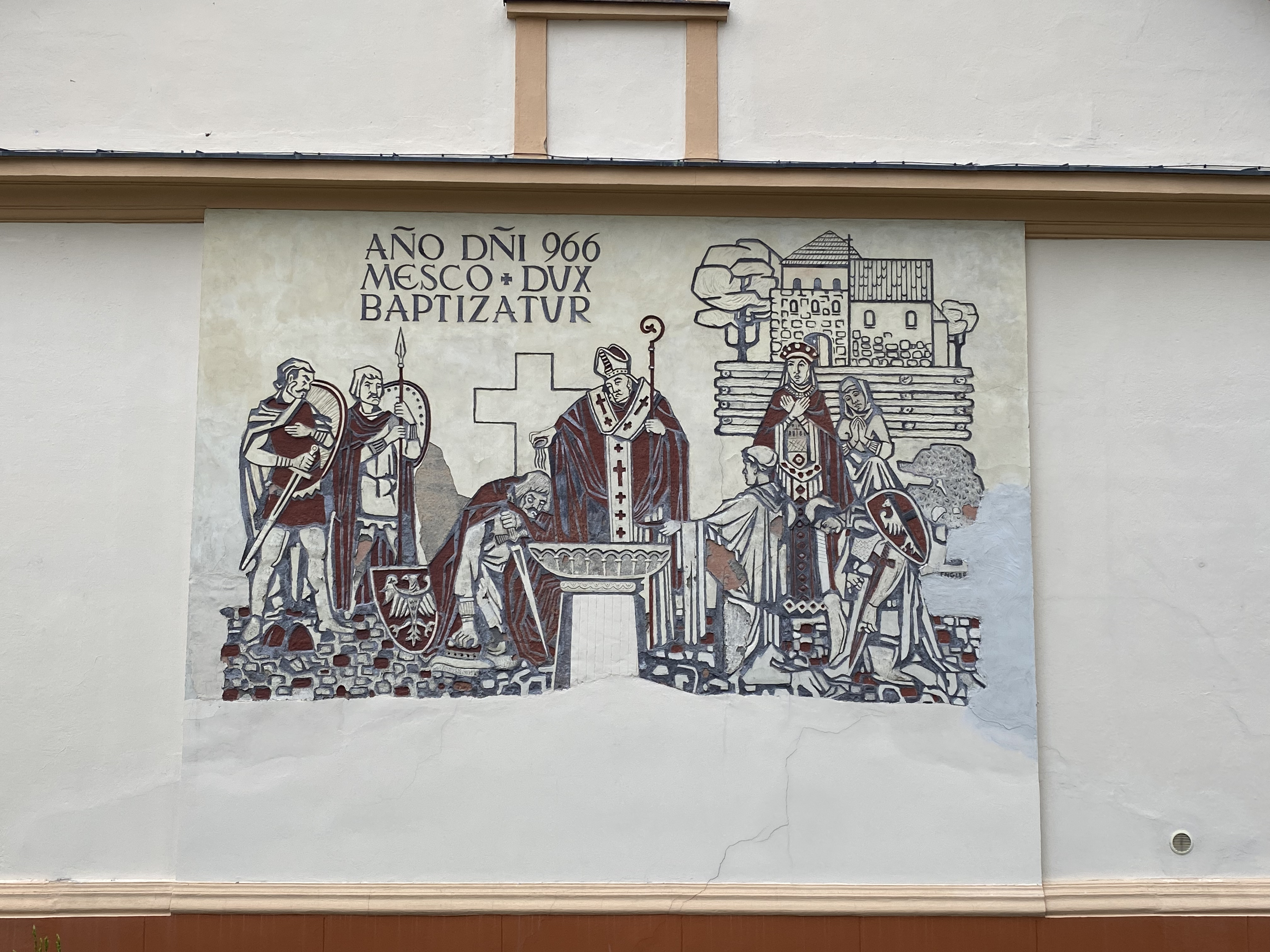

As written in the document: “To commemorate the Christianization of Poland, dated 14 April 966, given the momentousness of Mieszko I’s decision, considered as the beginning of the Polish State.” Thus, the beginning of statehood was associated with the adoption of Christianity by the ruler and his followers (not the whole community, and even less not the nation, as these, are thoroughly modern categories). It is no coincidence that the establishment of the holiday took place during the rule of the conservative, national-Catholic option, which declared its attachment to Christian values. And just like all religious holidays that become state holidays, in this case, it becomes exclusionary for all those groups that do not fit into the vision of the world represented by the representatives of power. These problems are clearly shown by the results of the vote, in which the document was accepted by a majority of 227 votes in favour against 125. In favour was the ruling coalition together with Kukiz15 and non-aligned MPs, while against was a significant part of the opposition.

Even more interesting is the history of the entire legislative process, dating back to work on the bill until 2017. The bill submitted on March 7 of that year (no. 1456) was more extensive than the one approved (see here). The document begins with a longer justification: “To commemorate the baptism of Poland performed on April 14, 966, considering the momentousness of Mieszko I’s decision, the civilizational significance of this event, the crucial importance for the development of our Fatherland, and at the same time the marginal presence of this historical fact in the social consciousness...” Thus, the celebration is placed in the perspective of the present day and the historical policy of the conservative authorities. The key element here is the marginal presence of the memory of the Christianization of Poland in the collective memory. The establishment of the state holiday is supposed to change this situation. Even more interesting is the proposed article 3 of this law. It says directly: 'It is a day of national reflection on the heritage of our fathers, on the responsibility of all state authorities, all citizens and each individual for our Fatherland, for its future and its prosperity. This holiday should serve to inspire action for the common good". The use of the communitarian category of ‘common good’ is, of course, a slogan that would be worth supporting. However, the earlier references to “the heritage of our fathers” point to a patriarchal understanding of the past by the conservative ruling party. This is the situation of today.

From a historical point of view, two issues are interesting. The first point is the link between the state and religion, and the second is the celebration of anniversaries of anniversaries and celebrating by referring to previous celebrations.

While the 1966 celebrations brought about a clear division between the state (the celebration of the millennium of Polish statehood) and the Church (the celebration of the millennium of baptism and Christianity), today these two dimensions are merging. Christianity becomes the key to statehood. On the other hand, the interpretation in which Mieszko used Christianity instrumentally to achieve certain political goals disappears. What is even more absent is the perspective of the wider community of Polans, which did not submit to this process of Christianization, while the full (whatever that would mean?) conversion to Christianity still took centuries.

No less interesting is the fact that for all kinds of anniversary celebrations - as was evident in 2016, when the 1050th anniversary of the “Baptism/Christianization of Poland” was celebrated – we refer to the 1966 celebrations. They became the marker of a kind of breakthrough in thinking about the presence of religion in public space. And it is so to this day, which after 1989 became a sign of a new political reality and character of the public sphere in Poland. While 1966 was marked by tension and clear conflict between the party and the Church, after 1989 these obstacles disappeared. Thus, the celebrations – religious celebrations, of course – mark the collective horizon of anniversary celebrations, while politically they find support in the form of conservative power.

Anniversary celebrations and historical references are always playing with the present day, the voters, and the society. It has little to do with the past, which can be used in any way. Historical politics in its anniversary edition – which seems interesting – feeds on other anniversaries. The history of various celebrations overlaps (see here), and earlier anniversaries are sometimes the only real historical reference points in the past.

A.K.